Lessons from three Black Belt projects in a make-to-order environment

Introduction

Most supply chain problems present themselves as operational issues: missing material, late deliveries, or too much inventory. In practice, these are rarely parameter problems. They are system problems.

Across different contexts and growth phases, I have learned that sustainable supply chain performance is not achieved by tuning reorder points, expediting transport, or pushing inventory down. It is achieved by designing systems that can absorb variability, make problems visible, and support decision-making under uncertainty.

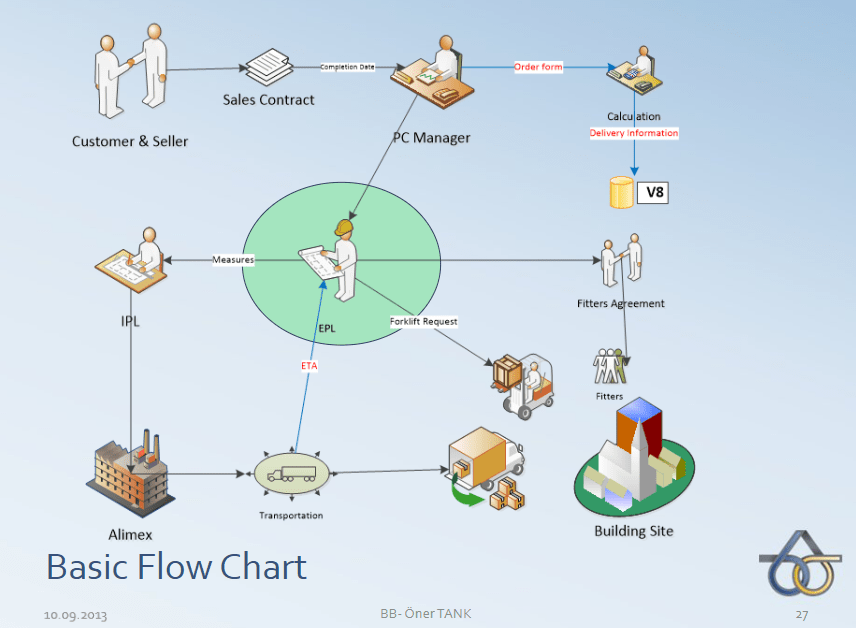

The reflections below are grounded in practice, drawing on three Black Belt projects at Alimex. The projects were different in nature, but they all pointed to the same conclusion: when the system is right, performance follows; when it is not, local optimisation only moves the problem elsewhere.

Systems before optimisation

In make-to-order environments with high product variety and demand variability, optimisation often starts too late. Teams measure shortages, delays, or firefighting effort and then try to “fix” them with local rules.

In one of the projects, aluminum profiles were the main constraint. There were more than a thousand profile types, long and highly variable lead times, strong seasonality, and rapid growth in overall tonnage. Production planning was struggling, and delivery reliability suffered. The natural response was to improve reorder point logic and count missing profiles more closely.

What became clear very quickly was that counting shortages is a lagging indicator, not a control mechanism. The real issue was not a wrong parameter, but the absence of a system that could cope with variability in mix, volume, and lead time.

The first step was therefore not optimisation, but system understanding: measuring performance in a way that reflected flow and variability, making trade-offs visible, and accepting that some problems cannot be solved sustainably without changing the underlying design.

Why Lean and Six Sigma must work together

These projects also reinforced a recurring pattern: Lean and Six Sigma solve different problems, and neither is sufficient on its own.

Lean thinking helped remove obvious waste, clarify flow, and create visibility. It made problems explicit instead of hidden in buffers, manual workarounds, or informal optimisation by individuals.

Six Sigma provided the discipline to test assumptions before acting. In several situations, what “felt” like the root cause was not supported by data. Without that analytical rigor, it would have been easy to change settings, add buffers, or introduce rules that improved one metric while degrading another.

In practice:

- Lean made the system visible.

- Six Sigma helped identify the true contributors to performance.

- Systems thinking guided what should actually be changed.

This combination prevented fast but fragile solutions.

Scaling is a system property

Another consistent lesson was that scaling is not an operational effort; it is a system property.

After production was moved from Sweden to Turkey, the Swedish market experienced severe delivery issues. On-time delivery to customer sites was below 30%, and international transport was often blamed. Geography, distance, and external partners became convenient explanations.

When the end-to-end value chain was mapped with all stakeholders involved, a different picture emerged. There was no shared lead-time model and no clear ownership across stages. Commitments were implicit, and delays accumulated silently until the final delivery date was missed.

By breaking the total lead time into explicit stages with clear responsibility—measurement, design, production, and delivery—the system changed. Reliability improved not because people worked harder, but because expectations, ownership, and interfaces were designed explicitly.

Once that system was in place, scaling demand became a capacity and planning question, not a recurring crisis.

Supply chain as a financial design choice

Inventory is often treated as an operational topic. In reality, it is one of the most tangible expressions of how uncertainty is handled in a system.

At Alimex, Days Inventory Outstanding was around 120 days. Reducing inventory was an obvious goal, but pushing stock down without improving availability would only shift risk back into operations and customer service.

The work therefore started with differentiation, not reduction. Inventory was segmented into runners, walkers, strangers, and obsolete items. Supplier relationships were redesigned to introduce kanban buffers both at supplier sites and internally. Availability was stabilised first; only then was inventory allowed to fall.

Within six months, DIO was reduced significantly—not through pressure, but because the system absorbed variability more effectively.

The broader lesson was clear: inventory is not waste by default; undifferentiated inventory is. When supply chains are designed properly, working capital improves as a consequence, not as a forcing target.

From projects to principles

The three Black Belt projects were different in scope—material availability, delivery reliability, and inventory—but they all validated the same principles:

- Sustainable performance comes from system design, not local optimisation.

- Lean and Six Sigma are complementary lenses, not competing methods.

- Scalability is built into the system; it cannot be retrofitted.

- Supply chain decisions are financial decisions, whether explicitly recognised or not.

The projects changed over time. The logic behind them did not.

Closing reflection

Supply chains operate under uncertainty by definition. The question is not how to eliminate that uncertainty, but how the system is designed to respond to it.

In my experience, the most durable improvements come from resisting the urge to optimise too early, investing time in understanding variability, and designing systems that make good decisions easier than bad ones. When that foundation is in place, performance improvements are not only achievable—they are repeatable and scalable.

Special thanks to Mr. Kemal Önen from MATRIS Consulting for his valuable coaching, Kemal Onen | LinkedIn